Nitin Gadia and Leland Searles, Co-Recipients

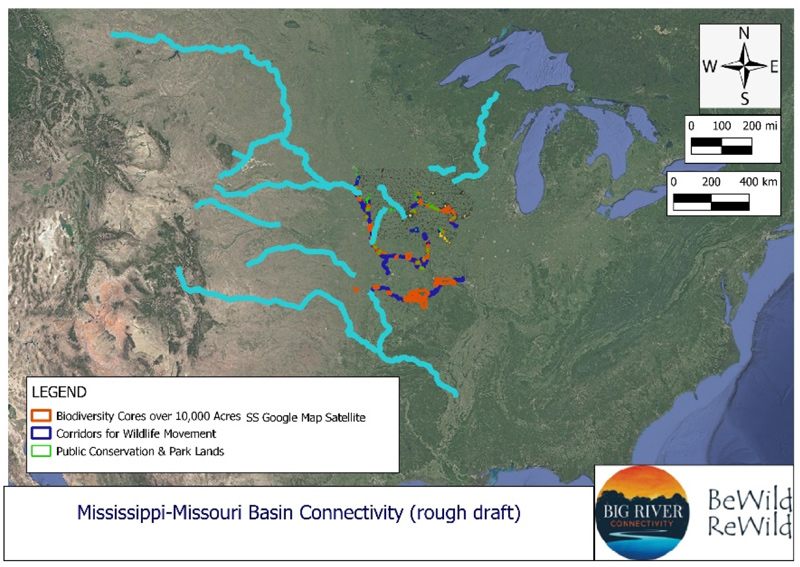

A three-month grant to Nitin Gadia and Leland Searles extends their mapping efforts to major river systems throughout the central river basins of the U.S. The Mississippi and Missouri Rivers are the “backbones” of this 32-state plan. The 2019 work has helped Nitin and me understand and overcome many challenges in geospatial map-making.

Several priorities will come to fruition. One is to place the ecosystems of the Prairie Region at the center of a much larger set of connections, by way of biodiversity cores and linking corridors. Another is to find downstream and upstream overland corridors to enhance the connectivity. Many downstream corridors are obvious and relatively easy to map, because they are at or near the points at which tributaries join a larger river. For example, in map work to date, these include the confluences of the Chariton-Missouri, Des Moines-Mississippi, and Iowa-Mississippi.

Many people have a chunk of our goals and vision in mind. A resident of the Loess Hills once played the old Cole Porter tune, “Don’t Fence Me In,” on the player piano in his parlor, with a westward view down the clopes of the Loess Hills… Later that day, we cut red cedar from his small piece of deep loess to make room for the prairie that belongs there.

A more challenging goal is to find overland routes between the headwaters of two rivers that eventually flow through different ecological regions. To date, one long overland corridor crosses northern Missouri from the Chariton to the Grand and to the Missouri in the northwestern part of the namesake state. This corridor includes core areas. Its purpose is to avoid the Missouri River in the sprawling Kansas City metropolitan area. In effect it joins the Ozark Plateau in the east to the Great Plains gateway at the west and the Loess Hills and adjacent Missouri River valley to the north.

Many people have a chunk of our goals and vision in mind. A resident of the Loess Hills once played the old Cole Porter tune, “Don’t Fence Me In,” for me on the player piano in his parlor, with a westward view down the slopes of the Loess Hills to the Missouri bottoms and the distant bluff in Nebraska. He said that the hills were the beginning of The West, what with the cactus, yucca, and other dryland plants, and he may have had in mind the middle stretch of the Missouri River, from St. Louis to Sioux City, as host for many westward-departing groups. Later that day, we cut red cedar from his small piece of deep loess to make room for the prairie that belongs there.

Another small corridor is located between the upper Chariton River and Whitebreast Creek, a tributary of the Des Moines River. Other overland corridors tie the Des Moines in central Iowa to the South Skunk and Iowa Rivers, as well as downstream to the mouth of Whitebreast Creek.

A possible overland corridor exists in the Great Plains, between the Niobrara River along the Nebraska-South Dakota state line; the Osage River and its tributary, the Marais de Cygnes; and the upper Kansas River. There are several large conservation tracts along the Niobrara and smaller parks and wildlife preserves along the other rivers. This connectivity restores the potential movements of animals and plants east and west by means of legs, wings, river flows, air flow patterns, and other processes.

The Arkansas River flows from the Rocky Mountains to the Lower Mississippi, where wildlife corridors potentially allow movement northward and eastward. It traverses a wide range of ecosystems. The Red River of the South ties in the southern Great Plains.

Interestingly, these watersheds also are music-sheds… As the music moved, even more so did the nonhuman life at one time. It will again, when we realize the importance of the natural world to our own fates.

Cores and corridors along the Big Sioux River tie the Midwest to the Subarctic and Arctic regions by way of the Red River of the North (in part, the Minnesota-North Dakota state line), as will corridors from Iowa’s eastern border to the Mississippi headwaters at Lake Itasca. The Wisconsin River connects the Great Lakes to the Mississippi-Missouri basin, as will the Illinois and Ohio watersheds, both flowing through the Eastern Woodlands and, in the case of the Illinois, through the easternmost part of the true Prairie Region.

Interestingly, these watersheds also are music-sheds, bringing together the Delta blues from Mississippi, western swing from Texas, cowboy tunes from the Plains, slave spirituals, southern gospel, ragtime from St. Louis, coal miners’ ballads from Appalachia, and more. I can imagine the movement of prehistoric arts and music along similar corridors. As the music moved, even more so did the nonhuman life at one time. It will again, when we realize the importance of the natural world to our own fates.

And even without us, all this other life has an importance no human can overestimate. The goals and vision of the Big River Connectivity mapping project are to spread this perspective and the actions to bring it about to a larger audience. Let the vision blow with the wind, flow with the rivers, fly with the dragonflies, and pad its way quietly in the new snow.