- This forum is empty.

Iowa’s remaining woodlands hold much of our remaining biodiversity. This is because woods are associated with floodplains and steep slopes that are not so useful for either cities and towns or for agriculture. But these are rich areas to begin the process of rewilding our minds and regaining our natural biodiversity and, alongside these, rewilding our farmscapes to function in more natural ways.

Iowa’s remaining woodlands hold much of our remaining biodiversity. This is because woods are associated with floodplains and steep slopes that are not so useful for either cities and towns or for agriculture. But these are rich areas to begin the process of rewilding our minds and regaining our natural biodiversity and, alongside these, rewilding our farmscapes to function in more natural ways.

Our forests and small woodlands are homes to many kinds of birds, many colorful lichens, a range of mosses, crucial soil organisms, and the more obvious plants and animals. Insects and spiders live in woods, accomplishing flower pollination, building intricate webs, and feasting on the many food sources. Lacking natural predators, White-Tailed Deer take leisurely strolls, sometimes running with lack of haste from human intruders.

Walking along a paved trail in Ashworth Park in Des Moines one May, I held my binoculars up to sight the Northern Parula Warblers I heard high overhead. Black-and-White Warblers searched for eggs on tree trunks and branches, easily mistaken for Nuthatches because of their behavior. Small flycatchers flitted along the banks of Walnut Creek, identifiable only if they gave a short song. And there, in that tree, what is that one? An uncommon Yellow-Throated Warbler, a male, with its contrasting deep yellow throat and black-and-white face and black cap and eyeline.

Among the birds, there is a variety in size, colors, and food strategies: from tiny Ruby-Throated Hummingbirds (the smallest, a nectar feeder) to the largest, the Broad-Winged Hawk and Great Horned Owl. For food strategies, there are insectivores (Brown Creeper, flycatchers, mimics – the Catbird and Brown Thrasher, orioles, small hawks, vireos, warblers, woodpeckers), carnivores in the narrow sense of that word (hawks, owls), omnivores (American crows, blue jays, cedar waxwings, thrushes), piscivores (eagles, Belted Kingfisher), and seed eaters (buntings, finches, sparrows). In turn, the medium and small ones become prey larger ones, as well as lucky ground-based mammals.

Another spring in Ashworth Park, I heard an unfamiliar series of hawk calls and moved toward them. The pair of Broad-Winged Hawks finished mating, and one took wing and made for decent photos in the blue gap of the tree canopy overhead. I felt honored to witness what seemed to be a mutually happy event for the two birds. In a different year, a dark-eyed Barred Owl watched me with what seemed to be fierce anger as my camera came up for a few photos.

Everything in the woods is potential food. Mosses take nutrients from the rainfall as it trickles down the bark of trees and splashes on the soil from the dripping leaves. Fungi digest tree bark and organic soil material and decaying logs and hapless insects. Nut-eating chipmunks and squirrels leave opened hickory and walnuts that mark their meals for several years. These same rodents go out on oak limbs in late summer to take acorns from the branches, raining debris on the forest floor and passersby. Deer browse basswood suckers, jack-in-the-pulpit, Virginia wild rye, and much more. Opossums consume insects and other arthropods, including ticks. Those unidentifiable flycatchers (and others, more suited to a beginner’s eye) perch on a bare twig and twist their heads, then dart out to snag a flying insect, and immediately reverse flight to the same perch. Owls capture forest rodents, choking down the entire mouse or the flesh of a squirrel, then coughing up a pellet of fur and tiny bones.

When I find an owl pellet, I take time to pick the pellet apart, placing the tiny bones back in anatomical position. Wait, there are two skulls and two right pelvic bones. An entire mouse and part of another. Judging from the teeth and the fur, these were white-footed mice.

Possibly the most frightening carnivore in an Iowa woodland is the short-tailed shrew, fortunately also very small. It must eat about every twenty minutes, about twenty times its body weight in a day, to feed its frantic metabolism. What is more, without food in its stomach, the stomach acids can digest the shrew from the inside out. One summer I collected rodents for an urban study and found the shrews in terrible condition when I return to the laboratory.

Least Weasels leave small prints in soft mud along a stream, present but not often seen. Once, I saw one in its pure white winter coat scurry across a paved road, looking like a tiny stuffed animal being pulled on a string.

And then there are the woodpeckers, those birds whose heads and skull muscles are uniquely suited to hammer on bark and wood. They range from the small Downy Woodpecker to the crow-sized Pileated Woodpecker. While Downies wander well out of the woods, sometimes to open up corn stalks for grubs, the larger Pileateds prefer large, mature stands where they are relatively undisturbed. I have seen them in two or three places, but more often I know of their presence from the two- to three-inch long, oval holes they drill into dead or alive but hollow trees in search of food.

Many acres of our woodlands are found on privately owned land, a contrast with true remnant prairie, much of which is on public land. Occasionally, prairie remnants turn up to a landowners’s surprise. Significant tracts of biodiverse woods are found on publicly held lands, but not all. Yet, most of the forests probably have been cut at least once, especially those in county-managed lands and state parks, and it’s possible to find rusting automobiles, non-electric clothes washers, old culverts, building foundations, chunks of concrete, and more in them, as though these were “waste ground.” They are not. These woodlands are vital to the longterm existence of biodiverse habitats throughout the state.

I will admit that, as much as I hate the junk and litter, at least the old junk has its own fascination. One time, I happened upon several cars in a stream valley. For the first time, I saw the odd appearance of a Ford flathead V-8 engine.

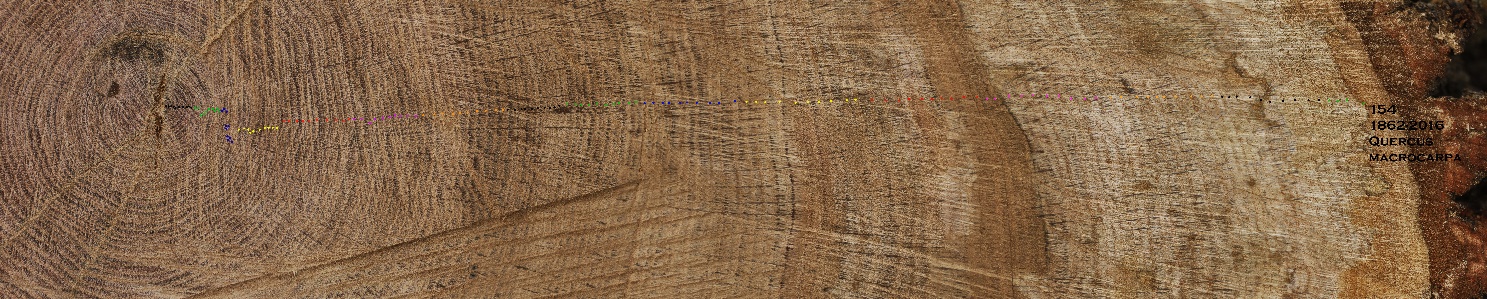

Some state lands in the Driftless and in south and southeast Iowa still may contain old-growth forest, but the oldest living white oak known (Pammel State Park) is younger than serious European settlement and the likely sounds of settlers’ axes and saws, taken for barn and cabin building, cabinet-making, firewood, and railroad ties. The oldest known white oak of all time from Iowa is dead, at about 500 years old, a slice of its trunk warehoused at the State Historical Museum.

In April 2012, I studied tree rings in southwest Des Moines, after a straight-line wind blew a number over. The oldest were white oaks, and the oldest of them was a seedling in 1857. My conclusion was that the area had been logged extensively, maybe even clearcut, in the 1850s to 1870s. Apparently all the living oaks in that neighborhood, Salisbury-Oaks, were younger than the 1850s, including the trees that the wind toppled, thereby becoming my specimens. Annexation to the city and residential development after 1860 allowed the woods to regrow and become old, by human standards. But these are not ancient oaks, and their similarity in age (within about two decades of each other) makes them susceptible to death from disease or “old age” in a matter of a few years. There are few to no seedlings, saplings, or young mature trees in the neighborhood, and not even in Ashworth and Greenwood Parks.

I’ve chopped and split firewood and driven wedges down 8-foot lengths of trunks to make rail fences and carved spoons from eighteen of the Midwest’s woods. There is almost nothing like this work to teach a person the different qualities of Iowa’s hardwoods.

Freshly opened Black Walnut has a purplish sheen that eventually turns brown, and the aroma has a warmth to equal the color. The off-white sapwood of a walnut log decays quickly, leaving the brown interior to lie on a forest floor for quite a few years. Whether in the interior of a twig or at the center of large log, a walnut’s pith consists mostly of air, with thin sections of pith creating little chambers. And the thick syrup from walnut sap is as good, maybe better, than New England maple syrup.

American and Slippery Elms have many diagonal fibers that can cause a wedge or axe to become pinched, requiring considerable effort to free it; a split along a section travels away from the starting point so that the resulting fence rail is thin at one end. Both burn with good heat in a stove during the winter. As a youth, I accompanied my mother and step-father into southern Iowa woodlands to gather morel mushrooms by the garbage bagful in the rotting elm duff, something that others say is still possible over forty years later.

Osage-Orange (Hedge-Apple or Bodarc) and Red Mulberry are an intense yellow, suggesting their botanical relationship, but one is soft and subject to rot – mulberry – while the other was used to fence cattle pastures as thorny live saplings and for rot-resistant fenceposts, among other applications. I imagine the hedge-apple, the fruit, as a giant, inedible mulberry, and the reverse – a mulberry as a tiny osage-orange fruit. Despite the osage-orange’s reputation as an excellent bow wood, the one I trimmed and shaved from a blank snapped at a hidden flaw, revealing its brittleness if the forces of flexion are uneven.

The wood of oaks is famous for its strength, resistance to rot, and relative ease of splitting for the winter warmth gained from a couple cords, stacked neatly. In the central valley of Oaxaca, Mexico, a local species has been overharvested to make fantastical wooden figurines called alebrijes; these resemble a dog, lizard, or other familiar creature – or not – but they are always painted, often delicately and intricately, in a blaze of colors and patterns. The different aromas of oaks are a joy among the smells of wood, with Northern Red Oak being a personal favorite. In several parts of North America, the acorn nuts provided food to the First Peoples. Some acorns had to be ground and leached several times to remove the bitter tannins, before they were further ground into a nutritious meal. The tannins also offered dye agents for hides and yarns, usually giving dark blues and purples, depending on the mordant.

In addition to the basic moisture differences in forest ecosystems (dry, mesic, wet), there are about nine recognized subecosystems: upland oak-hickory, maple-oak-basswood (high slopes and damp ridges), riparian hardwoods (elm, hackberry, buckeye, black ash, cottonwood, red oak), wet riparian woods (mainly black willow and silver maple), cedar glades (on exposed bedrock in eastern Iowa), mixed conifer-hardwood (Driftless Area), a native stand of Balsam Fir, and one or two others. An often-overlooked ecosystem is Oak Savannah, a mix of scattered oak (mostly Bur, sometimes White), prairie, and woodland plants.

To illustrate the biodiversity in the woods, there is a species of mining bee (genus Andrena) that usually is the first insect pollinator to appear in the spring. It shows up just before the Spring Beauties bloom and feeds on their nectar. Because the pollen of that plant is pink, these bees accumulate the pink pollen, rather than yellow pollen, and look almost psychedelic in closeup views. But they are small and easily overlooked. I’ve watched these bees ignore the blossoms of Bloodroot, Downy Yellow Violet, False Rue Anemone, White Dogtooth Violet, and other early spring plants as they seek out only Claytonia virginica.

I can only hint at the richness of our woodlands with these examples and recollections. I have not even written about the various fungi, other than mentioning lichens, that live as part of a healthy Iowa woodland: Autumn Oyster, Ceramic Glaze Fungus, Dryad’s Saddle or Pheasant-Back, Panther (a kind of Amanita, and toxic), Pinwheels, Russulas, Spiny Puffballs, Split-Gills, Sulphur Shelf or Chicken Mushroom, Tree-Ears, Turkey-Tails – and the morels. They require another day, or perhaps an entire book. As do the lichens.

Not long ago, while peering through a microscope at a moss sample, I saw a different plant. I could not find it among my books about mosses, nor in a botanical key to this group. It turned up in the last section of one moss book that happened to include a section on hornworts and liverworts: genus Frullania, one of very few liverworts that does not grow on soil. Only a few inches away were three kinds of lichens and other mosses.

In a planting of trees that had grown to mature sapling size, an odd smell of sickly sweetness entered my nose. I couldn’t determine what it might be, until I saw a busy honeybee hive overhead. The honey in that or nearby stash had fermented.

Walks in the woods rarely include good aerobic exercise for me. There is too much to see and think about, too many smells, too many acorns to taste in search of a less bitter tree, too many lichens and mosses, and, in season, too many warblers to spot. And beyond the objects heard and seen are the webs of interaction that connect all these living and nonliving things to each other. The possibilities for a new discovery or a memorable encounter are ever-present. On a chilly March day, a thick layer of moss disturbed may produce a surprised spider. I have learned to sample carefully and walk lightly in the midst of this vibrant world in which humans, their dogs, and trees are only the most obvious beings.

Leland Searles

Marshalltown, Iowa

March 2020