- This forum has 0 topics, and was last updated No Topics by .

We are living in the wake of wildness. We live in the highest extinction rate in 65 million years and don’t know what that means. We hear paradoxical predictions as we struggle to connect worldwide weather with where we live. Never in human history have we lived in a wilder, more unpredictable time and place.

We are living in the wake of wildness. We live in the highest extinction rate in 65 million years and don’t know what that means. We hear paradoxical predictions as we struggle to connect worldwide weather with where we live. Never in human history have we lived in a wilder, more unpredictable time and place.

Humans have always trusted the diversity of wildness to feed us even if we believe we grow our own food. As our relationships to wildness and food become separated, our safety and security diminish into fear, anxiety, and more attempts to control. In a city, suburb, or rural refuge, it is wildness that feeds us.

If we can’t relate to wildness where we live, then how will we relate to wildness somewhere else? All places are in need of wildness recovery, as we are ourselves. The wildness in our stomachs digests our food. We don’t feed ourselves. Perhaps the search for wildness and what we eat will provide some food for thought.

I searched decades for wildness, immersed for weeks at a time in the places we call “wilderness.” I never could feed myself with what was around me. I had to leave and found myself rooted in the most agriculturally productive place, ground zero, the front line in the most biologically altered state in North America, Iowa. It is, in a sense, a place and time where humans have never been before – the wildest place in the world.

I grew up moving every few years to various states across North America and other countries and visiting wild places. I see now how wildness has followed me and continues to grow inside me. This wildness exploration has taken me on a journey of wanting to be rooted, then finding a home and loving my deeper relationship to place.

The divisions of places into cities, agricultural zones, and wilderness areas disconnects us from the very wildness of how and where we live. We make up maps with artificial lines to put our priorities into their rightful place so they can be managed. We believe we can control wildness but we can’t. It can only be lived in and loved.

We believe we can save the wilderness areas, cut emissions, eat healthy, and connect the concerns of conservation. We think of misty mountains, seashores, deserts of solitude, and fantastic forests as being wilder places than where we are. We want to visit wild places, live near them, and find our food somewhere else. It is as if we can’t realize where we are not.

Some brilliant people and organizations have focused on how to protect and restore these remaining, undeveloped places. We want to connect wilderness areas and parks for their health and ours. But, a biologically diverse wilderness, which includes large predators, requires a landmass much larger than any park. This means people must be part of the picture and we can’t cut the picture into separate pieces or eat it.

These hopeful visions to ensure the flow of genetic material across the landscape have traditionally focused on both coasts. The West Coast sees their wild areas as less developed with a greater chance to protect what’s left. The East Coast sees a healing landscape with high potential to restore species diversity. This leaves out the land of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers which connect the two. What happens here — what is sacrificed here for someplace else — affects us all and everywhere.

We see symbols such as cougars, wolverines, wolves, and bears on websites — creatures few of us ever encounter. We understand saving land and protecting some predators. We can relate to coyotes, foxes, and deer walking into our neighborhoods. We want these wild beings if they can be contained to their place without threatening us, our property, or pets.

As this separation slices species into places and priorities, we remain trapped in human domination. This control and conquest of the landscape diminishes life and our visions of what is possible. Once we want “wilderness areas” and not wildness, we have lost our place in the land. We need a deeper understanding of our place and what we eat.

In this world of wildness, we all have to eat something. We designate places of importance as having more wildness or producing food security. We prioritize what life forms are important to keep and which are not. We tend to call some areas sacrifice zones and reduce them to specific outcomes such as agriculture. What happens in these agricultural zones sets the policies of conservation and land use everywhere.

The biological diversity of the Midwest ecosystem of grassland prairie was comparable to the species diversity index of the Amazon rainforest. Now having converted diversity into monoculture malpractice, we are consuming the very soil itself. This is where the sixth mass extinction has already hit the ground and we are waiting for the climate to catch up.

As Lewis and Clark’s world view of wilderness struggled westward, they were lost. All they could recognize was where they were not. This blindness to wildness diminished diversity and led to monocultures and genocide. Our food production here is still living off the carcass of that wildness.

We know little of the human relationships that resided here for thousands of years before us. The little we do understand of First Nation people is best heard in the phrase “we are all related.” They had time to record the passing of centuries in cultures connected to place and the stars. Our present view leaves fewer stars visible and a future we can’t comprehend except through crisis management.

All their needs were met locally. They lived in relation with what they ate and what ate them. Their language spoke with bears, eagles, rivers, and plants as family. How do we understand where we live except from our recent, European-bred perspective? That sees nature for recreation, services, or resources for us. We act as if we are in charge and know what is best but disregard the more-than-human world as not part of ourselves.

The first European explorers in Iowa said things like — “there are so many fish you could walk across the river on their backs; you could throw a stick in a tree and knock down two turkeys; we filled our farm wagon in a few hours with prairie chicken eggs.” Today, the big business of agriculture dominates our quest for security while requiring Iowa to import roughly 85% of what we eat from an average of 1,500 miles away.

Ironically, we are still people of the corn and critters we directly depend on. Midwesterners like the sound-bite — “we feed the world.” We are considered one of the top producers of animal feed, beef, pork, turkeys, chickens, eggs, milk, cheese, corn, soybeans, ethanol energy, sweeteners, and oats. I venture much of what other people eat also comes from faraway and is being mined on a level few of us understand. I bet you eat a part of where I live almost every day.

I know people can live in the same place, look out the car window, eat the same food, hike the same path, and see things differently. Today, there is limited literature related to overall land use policies, procedures, and outcomes that focus very far in the future. Much of the information coming out of universities and government agencies are specific studies or projects. They assist people in managing for “pests,” monoculture crops, and market desires. They focus on minor cuts, abrasions, and cosmetic changes while our understanding of wildness and collective health is ignored.

In 1989, Iowa hosted the International Environmental Ethics Conference for the first time. It brought speakers from Iowa and other states and countries together to talk about wildness. We asked the question, “Does my homeland have intrinsic or instrumental value?” The clear choice focused my mind and changed my vision.

I thought I knew where I lived, but that question changed that. I hope I can change what you think. I began asking what have we protected, left wild, and allowed to heal? The first few generations of “Iowans” left little of its original ground cover.

At European settlement, Iowa was roughly 70% prairie. Today 99.9% is gone, 30,000 acres remain. The prairie birthed the fertile, deep farm soil. The remaining dirt and its health are still being mined. This requires additional inputs such as fertilizer and petroleum from elsewhere, making Iowa the leading contributor to the dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico.

Iowa was 10% wetlands, and today 98% is drained of possibilities. These ecosystems cleaned the water and nursed the wildlife we lived off of until they were gone. Iowa now ranks near the bottom for water quality. Iowa was 20% woodlands; now 80% is gone. We clear-cut the whole state, leaving no old-growth forests for education and beauty for the children of other species.

Iowa being the most biologically altered state in North America illustrates the direction humanity has moved. And yet, here on the lip of the last glacier I found wildness, love, a calling, and a language older than words. I love Iowa. Here is where we will answer the question, “What has value?”

I consider myself a naturalist. I’m not as good at it as most others were for thousands of years. With over 70 years of study, I have had to specialize in my own species. This leaves me baffled by the choices we make in where and how we want to live. I am still learning where I am now.

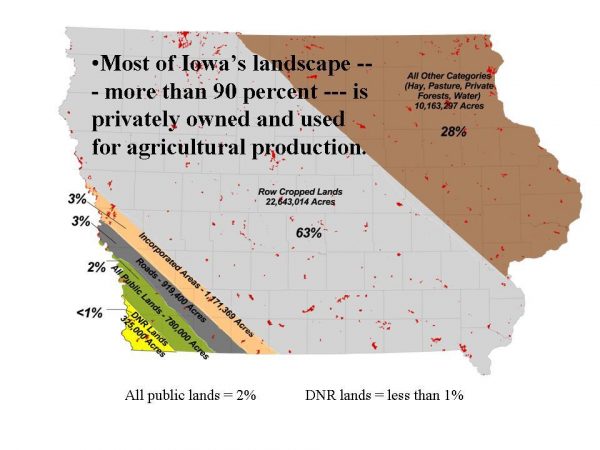

Iowa covers 36 million acres; and we Euro-American colonists have converted about 92% of it for agricultural usage. We have now covered 23.6 million acres, roughly two-thirds of the state, in just two annual species — corn and soybeans. Another 6% is taken for our cities and roads. Iowa is ranked 49th nationally in the amount of public land. Only 2% of Iowa is in public land — of which roughly 50% is in road right-of-ways.

Even if we combined all of Iowa’s federal, state and county areas and made them available as a biological repository, they would cover a square roughly 32 miles on a side. Inside this small square are many square miles covered in artificial lakes, non-native species, and other human developments. Only 10% of Iowa’s remaining prairies and forests lie within the public domain and its limited protection.

Iowa’s healing places are rare and are still being developed for their “resources.” After 30 years working for the Iowa Department of Natural Resources, I have walked, worked, wetted, and slept on the ground in almost every state park. I’ve explored the state managed forests, recreation areas, many state preserves, and some of the best, healthiest private lands in Iowa.

We started our park system in the early 1900s because there was little public land available and none left unaltered. All state parks were established from clear-cut, mined, plowed, or heavily grazed areas. And yet ironically by 1937, we were nationally acclaimed and led the country in the establishment of state parks.

Today, all 71 postage stamp state parks combined total about 56,000 acres out of Iowa’s 36 million or one-tenth of one percent. This is a square just over nine miles on a side. Almost all parks can be walked across in an hour and you are rarely more than a mile from a road. Farmers converted roughly the size of our state parks, or around 50,000 acres, of grassland, scrubland, and wetlands from 2008 to 2011. Urban sprawl has devoured another 50,000 acres in the last ten years.

Annual park visits have continued to climb, from 11.4 million in 1994 to around 16.6 million by 2020. With the Covid virus we are seeing even more usage. We mow hundreds of acres of non-native grasses to picnic and camp on while invasive species continue to expand everywhere. We continue expanding campgrounds and recreational uses within the remaining areas while few additions to parks are made. Increasing demand to use these “undeveloped” parks will insure more “development” and decrease biological diversity.

Henry David Thoreau stated the obvious, “In wildness is the preservation of the world.” It is the wildness we should be discussing instead of calling something wilderness or parks. A few years ago, public meetings were held across Iowa to determine what needed to be done to take care of our parks. Money and dwindling budgets were considered along with increasing park camping fees.

After an hour-long feast on what the public wanted, the overwhelming outcome was a long list of developments. We wanted more mowing, more trails and uses, more electricity, more lights, bigger campgrounds, bathrooms, and playgrounds. The most sensible financial solution offered to accomplish these “improvements” was to plant corn for income on parts of the parks we don’t use.

Surprisingly, the greatest support for parks comes from people who never go to them. They just know parks are important. Parks improve water quality in our lakes and streams. They preserve places of scientific importance and quiet beauty. They are “living” historical monuments and outdoor classrooms. More importantly, these parks symbolize our maturity as a state which recognizes the importance of placing limits on development now and for future generations.

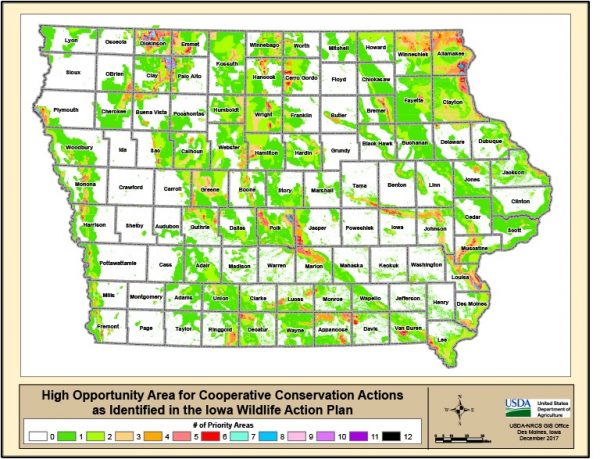

We must stop ALL development within these remaining core areas TODAY! We must begin removing much of the development that already happened. We need to provide real protection to these last scraps by designating additional land to surround and buffer them. And most importantly, we need to create greenways, blueways, or living corridors — REAL trails, some miles wide, to link these areas together so the flow of life and re-creation can continue.

Iowa now is a barrier for species trying to migrate or even adjust to climate change. Wild animals struggle to cross this monoculture madness of corn and beans without getting poisoned, shot, or run over. We don’t have room in this state for two wolves last year who found themselves here by mistake. Once every few years a moose or bear or even a lost mountain lion is killed as we provide no legal protection for them.

This applies to many other species also. For example, the Lesser Scaup duck, the most common diving duck in North America, is finding it extremely difficult to migrate across Iowa due to poor water quality and lack of food. Their numbers are dwindling as they starve to death or lose so much body weight they can’t reproduce.

As our water quality continues to deteriorate along with species diversity, the budgets for environmental programs have steadily decreased over the years. The prevailing political agenda is we must increase usage and develop parks in order to save them.

With so few places to get away from it all and experience the great outdoors, we find little left to exploit. The guiding philosophy is perverted into — we must get people out in nature so they can grow to love it and then they will want to protect it. We have been taking that approach for way too many years and are left with little protected for other species.

Every natural area in Iowa is isolated, separated as tiny islands that cannot maintain their biological diversity and health. They are losing their wildness and yet we are told the more use the better. Some say, if we can’t pay and care for these areas then we should get rid of them. Actually, we are, as parks will never pay for themselves in strict economic terms; nor will our rivers, our old trees, and our air.

Which path now? The way divides. We could choose the path not taken. We could allow for wildness even though we don’t understand quite yet how it sustains us and the rest of the world. We could be wilder ourselves allowing wildness to show us the way.

What kind of state do you want to live in? If the parks’ future and wildness depend on the few who vote, the outcome will be decided by politicians and profit, not life. What if everyone and every being voted? I think the trees, flowers, bugs, and birds would win. They might just leave us alone, hungry, and isolated in silence. Now that is wild!