- This forum is empty.

Iowa is home to over 100 species of dragonflies. They are beautiful aerial predators that help keep the mosquito population in check. Some species migrate long distances. Colorful adults are most familiar, but ALL dragonfly species depend on freshwater when larval. Many species spend most of their lives underwater where they are voracious predators, including small fish and amphibians. The Sand Snaketail is only found only in WI, MN, and Iowa.

Iowa is home to over 100 species of dragonflies. They are beautiful aerial predators that help keep the mosquito population in check. Some species migrate long distances. Colorful adults are most familiar, but ALL dragonfly species depend on freshwater when larval. Many species spend most of their lives underwater where they are voracious predators, including small fish and amphibians. The Sand Snaketail is only found only in WI, MN, and Iowa.

Photo by Diana-Terry Hibbitts

I grew up in the city, son of an Illinois farmgirl and a young man from Canton, China. My father used to say he just couldn’t see living in a city of less than a million people. Chicago was metropolis enough and that’s where my parents met. When I was a boy, my mom’s father still farmed his 250 acres near London Mills, Illinois and I loved riding his Fergus Ford tractor. My original appreciation of nature came from city parks, Cook County forest preserves, the shores of Lake Michigan, and farm visits. On the road from Chicago to London Mills we experienced epic thunderstorms, pork tenderloin sandwiches that overflowed the plate, and a coating of bugs so thick on the windshield we pulled over to wipe them off. On a recent trip from Chicago to Madison to Decorah, my windshield was final resting place for nary a nat.

You might not expect to see a Wolf, Wolverine, or Prairie Chicken, early victims of our relentless anti-biodiversity industriousness. But insects have been so common, abundant, and yes, pesky, that it’s hard to fathom that our collective activities –especially the way we farm and tend our yards—could make a dent in their multitudes. Insects, as my mentor E.O. Wilson was fond of saying, are among “the little things that run the world.” They drive natural cycles as food, predators, pollinators, and soil enrichers. Birds depend on insects for food, even nectar-loving hummingbirds need the protein they provide. The insects of the midwestern US rely on native prairie, woodland, and riverine plants, and in turn our nesting and migrating birds need those bugs. As news has come out about insect loss, the abundance of even common birds like sparrows have been on a parallel course of steep decline. The biodiversity crisis is an abundance crisis. As Americans, we should appreciate that. Life is big, wild, overflowing, and immoderate, like a traditional smorgasbord. I’m a proud ally of Big River Connectivity and Rewilding the Heartland, efforts at the vanguard of bringing the biodiversity smorgasbord back to Iowa and beyond, to the greater Mississippi River System.

Photo by Andy Morffew

The Mississippi River Watershed is unfathomably huge. A drop of water can travel connected waterways from Montana to Louisiana traversing 9 states in a 2000-mile-plus journey. Truly appreciating this watershed is tantamount to understanding the world and our place in it. E.O. Wilson wrote in Diversity of Life “Our troubles arise from the fact that we do not know what we are and cannot agree on what we want to be. The primary cause of this intellectual failure is ignorance of our origins. Humanity is part of nature … a species that evolved among other species. The more closely we identify ourselves with the rest of life, the more quickly we will be able to discover the sources of human sensibility and to acquire the knowledge on which an enduring ethic, a sense of preferred direction, can be built.” My work with the E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation and the Half-Earth Project seeks to help young people especially to better understand their place in the world and find their preferred direction.

Middle School science class

Like the Mississippi Watershed, the scale of biodiversity loss and what’s needed to reverse the extinction crisis is big and complex. The ground game for conservation is tough and requires never-ending effort and vigilance. Reversing biodiversity loss is a global enterprise entailing high-level political, economic, and institutional responses. But life on our planet is not evenly distributed, and every place has stewardship over a unique ensemble of living things that particularly thrive in THAT place. Your very own beloved and cherished places. Action we take today —protecting undeveloped landscapes, eliminating invasive species, restoring native plants in yard and farm— starts paying a dividend tomorrow and then on to future generations. Rewilding is fun, satisfying, and life-affirming.

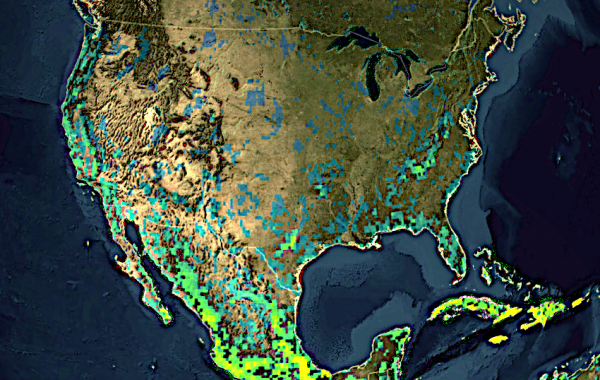

My immigrant father loved big cities, but he was also taken with the vast American landscape and driven to explore it with his family. We would load up our 1966 Volkswagen Camper to visit state and national parks from Maine to Oregon, Wisconsin to New Mexico. The rangers of our National Parks were like gods to me, full of wisdom I yearned to earn. Today, I understand better the complex legacy of these beautiful landscapes, how we displaced native communities, and how these lands were chosen for scenic beauty, a lack of “practical” value, and not primarily to preserve biodiversity. Maps can help us see the world by displaying all kinds of information. A map of biodiversity and conservation areas in the US reveals that we’re not generally protecting the most important lands for biodiversity. Adding a map layer of agricultural intensity in the US reveals the enormous footprint of that human activity. To restore biodiversity and the essential natural processes we depend on for drinkable water, breathable air, nourishing food, and mental health will require protecting, restoring, and connecting biodiversity in the Midwest. A vast and laudable rewilding project.

Static image from the Half-Earth Map with unprotected areas rich in biodiversity blue & green

Most of us attend to our own personal needs and concerns, and to problems that are right in front of us and feel immediate. Bernd Heinrich, a keen naturalist famously fond of owls and other birds writes, “Owlhood is not likely to be served by ministering to an owl. Helping an owl affects one owl, and that is all. One can help more owls by buying an acre of forest and keeping it wild than by preserving all of those who run afoul of fate, or with civilization. But you do not see the former, or at least you cannot touch them and point your finger and say, “Yes, I helped this owl.” The unseen, statistical owls are all too easily neglected. I believe that the accelerating erosion of our natural world can be ultimately traced to our inability to see statistical owls. We are mesmerized only by the real ones.” We should care about statistical owls and other creatures because our very lives depend on intact nature. I want everyone to join us in the effort to rewild Iowa and ultimately all of our precious planet, each in their own way, enabled by their particular circumstances. Some will join us because of a particular plant, animal, or place they find beautiful. Others may find their biophilia starting with a pet or a houseplant, but then come to see deeper connections, and drink more deeply from the well nature offers. Once that happens, to paraphrase Ed from his book Letters to a Young Scientist, I will “urge you to stay on the path you’ve chosen, and to travel on it as far as you can. The world needs you – badly.”

Pingback: E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation » A Sense of Direction